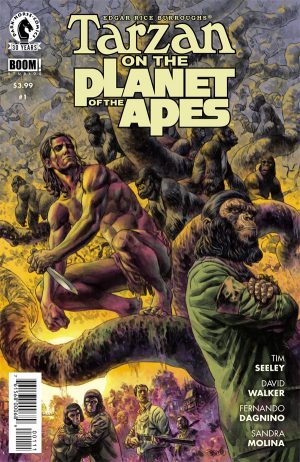

We all know Planet of the Apes. Or at least we all know its twist ending, we all hate the Tim Burton remake, and we all have mixed feelings about the James Franco one. We also all know Tarzan. Dark Horse Comics in collaboration with Boom! Studios present the first ever crossover between the two franchises in Tarzan on the Planet of Apes. Where the creative team of David Walker (Power Man and Iron Fist), Tim Seeley (Revival) and Fernando Dagnino (Suicide Squad) bring to answer just how you unite the 1960s dystopia science fiction of Planet of the Apes with the colonial pulp fiction origins of Tarzan. David Walker was gracious enough to talk with us about his love for Planet of the Apes and just how you go about presenting Tarzan for a modern age.

Patrick Larose: You’ve talked in the past about important and influential a series Planet of the Apes was for you, and I know for me, growing up, it was so surprising how malleable and weird the original film series was and how many different kinds of stories they were telling. What was it that made it stick with you for so long?

Patrick Larose: You’ve talked in the past about important and influential a series Planet of the Apes was for you, and I know for me, growing up, it was so surprising how malleable and weird the original film series was and how many different kinds of stories they were telling. What was it that made it stick with you for so long?

David Walker: I saw those films when I was very young, which is to say that I saw them back before the original Star Wars came out. Planet of the Apes was my Star Wars – it grabbed hold of my imagination, and never let go. A lot of people don’t realize (or remember), that before the ancillary marketing craze of Star Wars, with the toys and the comics a the trading cards, there was Planet of the Apes. So, here you had these movies that lit the fire of my imagination, and then all this other stuff that fueled the fire. I owned all the POTA comics, I read them over and over again, and it was through this series that I was introduced to the principles of storytelling. This was a huge part of leading me down the path of what I would grow up to be.

PL: Nighthawk is such a phenomenal, poignant take on so many troubling events and topics going on right now like police violence and systematic oppression. Given how strong your commentary was there, for those following your writing here, what part of society are you interested in highlighting with this story?

DW: Tim Seely and I, along with our editor Scott Allie, really talked about what it was we were trying to say with this series. The original POTA films were all statement movies, and all of them were pretty dark and grim. We knew all of this going in, and we knew that if there was going to be any “truth” or credibility to the Apes side of the story, it had to come from whatever underlying message we put forth. Ultimately, it is a story about defining what it means to have humanity, versus simply being a human. It is about empathy and revenge, and the path we often walk that doesn’t feel like out path, but a path someone has forced us to walk. In the end, we really tried to explore the dangers of “us-versus-them” thinking, and how ideologies can be dangerous if empathy is not present.

PL: Tarzan, as he was created in the early 1900s, is such a character founded in these really problematic tropes like the white savior complex so how do you manage to reinvent him for the modern age? What was your thought process in navigating between the pulp elements that define Tarzan while avoiding those outdated and troubling elements?

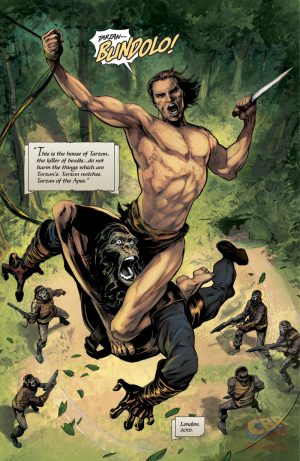

DW: I can’t lie, Tarzan was difficult to wrap my head around, and I think it was the same for Tim. Neither of us wanted him to be that white savior trope, wrapped in the tenets of white supremacy, Eurocentric colonialism. For me, I decided to think about how I would write a Tarzan comic that wasn’t a crossover with Planet of the Apes. And like I said, it wasn’t easy. I loved Tarzan as a kid, and there is still a special place in my heart for him, but like James Bond, Tarzan is a hot mess of problematic thinking. Ultimately, the decision was to play around with who and what Tarzan thinks of himself, and how it informs his actions. Our version of Tarzan doesn’t think of himself as human; he is a member of the Mangani tribe of gorillas. He is not the Lord of the jungle here, so much as a confused human who thinks he’s a gorilla. And we play with this because much of this story is about what makes us human, what makes us humane, and what is required to assert and respect humanity.

PL: Given that with this comic, Tarzan is going to have a new backstory and story elements incorporating him more with the Planet of the Apes world, do you still have any plans on addressing any of the more troubling elements of past Tarzan stories? How did you and your co-writer and editor go about incorporating or responding to that Tarzan legacy? Things you went out of your way to avoid like will Tarzan still be going off to rescue a kidnapped Jane?

PL: Given that with this comic, Tarzan is going to have a new backstory and story elements incorporating him more with the Planet of the Apes world, do you still have any plans on addressing any of the more troubling elements of past Tarzan stories? How did you and your co-writer and editor go about incorporating or responding to that Tarzan legacy? Things you went out of your way to avoid like will Tarzan still be going off to rescue a kidnapped Jane?

DW: I want to be careful not to get into great detail, to avoid spoilers. But I will say this—we were very specific about what Burroughs elements we needed to use to make the story work, and what we could leave behind. Tarzan exists in what I’d describe as a very pure form – it’s like we used the most basic elements we needed to define the character, and then we placed that bad boy in the Planet of the Apes. One of the good things about Tarzan is that despite what can be viewed as problematic elements tied to his past – which must be viewed contextually – the character himself has a level of recognition that allows him to be stripped out certain baggage. I mean come on – you show a muscular white guy in a loincloth, surrounded by gorillas, and you know who you’re looking at. Tarzan is so old, and so well established, that it is possible to tell a story about him that isn’t overflowing with all of the things that make the gatekeepers of political correctness cringe.

PL: I think one of the both essential yet troubling aspects of Tarzan is the importance of Africa as a setting. He has to be in the jungle, but there’s no way it can still the gross, outdated place with incomprehensible and bug-eyed natives that Burroughs’ wrote about. Is the story still rooting itself here and what was your process in juggling both it being a Tarzan story slash a story with hyper-intelligent apes and it being a real place far flung from the descriptions of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ stories?

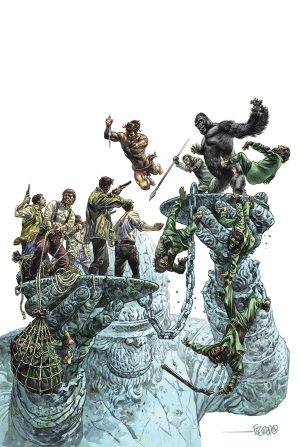

DW: The answer to that is fraught with spoilers. But I’ll do my best to explain. First, this is an alternate reality that aspects of the Tarzan mythology with aspects of the Planet of the Apes mythology. Creating these kinds of stories is frequently difficult. At the end of the day, this is more of a Planet of the Apes story that stars a very stripped-down version of Tarzan. Tarzan himself may come with all kinds of baggage, but that baggage isn’t part of this story. Some people might say we are cheating, but honestly, all of these franchise crossovers are something of a cheat. One of the great things about the original Tarzan mythology created by Burroughs is the Mangani apes. The Mangani were a crucial part in bringing these franchises together, and in my mind, one of the few parts of the Tarzan world we needed to keep. Again, some people may hate it, and call it cheating. But Tim and I, as well as Scott and his assistant Katii (who were incredibly active in helping shape this story), have done something that I think is entertaining. And the art is phenomenal.

PL: Having grown up with these characters and series, were there any characters here you were really excited to write for and were there any that were off-limits or you couldn’t fit into the story in some way?

PL: Having grown up with these characters and series, were there any characters here you were really excited to write for and were there any that were off-limits or you couldn’t fit into the story in some way?

DW: Honestly, I had no interest in Jane or anything like that. We were working with a limited amount of space, so there was never any argument about using her. I would have liked to worked a bit more with the Mangani, and character like Kerchak, but they had to limited in who much real estate we gave them. Still, Tim and I both worked really hard to become fluent in Mangani. I was most excited about the Apes characters – which was the main reason I came on board. This project gave me the opportunity to work with characters I absolutely love, and to take them in directions they’ve never gone before, whether it be in film or other comics.

PL: Often in crossover stories there tends to be more about mashing together two identifiable brands in spite of any thematic dissonance. What did you think were some important ideas or themes to preserve from both POTA and Tarzan while exploring new themes in a more 21st-century context?

DW: This the story of two beings raised as brothers – Tarzan and Caesar. One is a human that thinks he’s a gorilla, the other is a chimpanzee trying to lead his tribe to a place of being that defines them as more than mere animals. Tarzan is a human that is more of an animal. Caesar is an animal that is more of a human. That story is playing out every day in our headlines, as various people are robbed of their humanity, and denied various rights. Women are not treated as equals to men. Blacks are not treated as equals to whites. The poor are not treated as equals to the rich. This world, and this society, in particular is engaged in a war of ideology that seeks to define roles of superiority and inferiority, and doing so creates a system of oppression and dehumanization.

PL: Also, just to end this off, what’s your favorite Planet of the Apes movie and what do you think is the Planet of the Apes movie people need to see who have only seen the original?

DW: I love the original 1968 film. My favorites of all the sequels is Conquest. It is the only one of the original films that stands along as a story, and I consider it to be as politically incendiary as Pontecarvo’s anti-colonialist class The Battle of Algier. But more than that, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes is both an excellent science fiction film, political allegory, and one of the best films of the 1970s. It is dismissed as such, because of its genre and because it is a sequel, but it is the only other POTA film you can watch without knowing anything about the others.