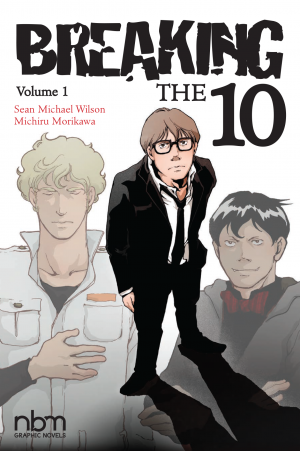

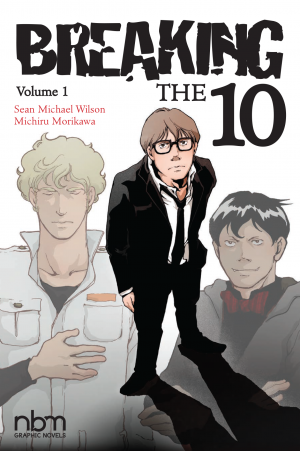

In my Warship Jolly Roger review, I clarified the difference between four-star books and what I usually would define as a five-star book. Usually, for me it comes down to a sharply handled book that has artistic ambition, either to move the medium forward in some way or to tackle subjects that go beyond the purview of general entertainment. Breaking the 10, a Western comic illustrated in a manga style, has ambitions. It is, at its heart, an exploration of the intersection between society and faith, a borderline blasphemous dialogue about the existence or non-existence of God, and the core question that seems to define for so many people the extent of their belief in a higher power: with all the pain in the world, does God even care? While the intent seems to come from a place of devout Christianity, Breaking the 10 cuts for the edge of faith, with crime, sex, and sacrilege brazenly displayed by our main character in his search for meaning. It aims to be more than a simple story, full of big questions with possibly unobtainable answers.

And this may be the dumbest comic I've ever reviewed for Bastards.

Let me clarify, dumbest, not worst. The plotting and pacing of the book are pretty competent, the first volume not a conclusion to the story but ending in the right place, the story building over time. The art, while sometimes lumpy and lacking meticulous definition, has some decent character work in it, and can't be credited as a detriment to the overall story. No, I've read worse. I've read E.P.I.C., Lone Star Soul, and you know, Zenescope. But search my memory banks with all the keywords you like, I honestly couldn't find a dramatic example of a comic that aimed so high intellectually and yet landed delicately like an innocent wind-plucked leaf in a field of philosophical ineptitude. Honestly, the next closest thing I could grasp for comparison is the socially conscious thrillers of Las Vegas architect Neal Breen like I Am Here...Now and Fateful Findings. Breaking the 10 isn't nearly as incomprehensible as Breen's work, but the blunt tone, shocking lack of grasp on its subject material, and most importantly, hilarious dialogue, made this book not a pain, but a unique joy to read, making me laugh more often and more deeply than any comedy so far this year, in any medium. Read this book. If you have time and a few bucks burning a hole, read it.

Let me clarify, dumbest, not worst. The plotting and pacing of the book are pretty competent, the first volume not a conclusion to the story but ending in the right place, the story building over time. The art, while sometimes lumpy and lacking meticulous definition, has some decent character work in it, and can't be credited as a detriment to the overall story. No, I've read worse. I've read E.P.I.C., Lone Star Soul, and you know, Zenescope. But search my memory banks with all the keywords you like, I honestly couldn't find a dramatic example of a comic that aimed so high intellectually and yet landed delicately like an innocent wind-plucked leaf in a field of philosophical ineptitude. Honestly, the next closest thing I could grasp for comparison is the socially conscious thrillers of Las Vegas architect Neal Breen like I Am Here...Now and Fateful Findings. Breaking the 10 isn't nearly as incomprehensible as Breen's work, but the blunt tone, shocking lack of grasp on its subject material, and most importantly, hilarious dialogue, made this book not a pain, but a unique joy to read, making me laugh more often and more deeply than any comedy so far this year, in any medium. Read this book. If you have time and a few bucks burning a hole, read it.

The book concerns an upper-middle-class schmo with a big house, a job that can afford him vacation time off, and one big problem: his wife and son just got killed in a car wreck by a drunk driver. A devout Christian, this sends him into an existential spiral, filled with resentment and rage aimed at the seemingly uncaring God that would ruin his life this way. His plan implemented immediately, is to lure God into revealing his existence (or non-existence) by methodically violating the Ten Commandments, sussing him out into the open with blasphemy and sin. This means committing petty crime, orchestrating adultery, all building up to the most memorable sin of all, which undoubtedly will serve as the climax when he attempts to kill the man who killed his wife and kid. All the while, his life is invaded by a pair of monochromatically themed slackers, each representing the dual extremes of piety and anti-authoritarianism, who engage him in lengthy debates on morality, faith, atheism, communism, capitalism, the moral obligations of those that reject civilization, and jokes about boobs.

Now here we get to the fun part. Nothing conceptually so far is awful, kind of on the nose, but a talented writer could eke something interesting out of it I imagine. There's a sort of tightrope walk between blasphemy and faith in the idea and presentation, sort of like what Kevin Smith worked with in Dogma, only with a joyless seriousness about the subject matter and without Smith's lifelong meditation on his Catholic faith. Here, you get a semi-Socratic dialogue as if conducted by Mac from It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia. To "covet you neighbor's wife," he forces himself to get a literal hard-on for his female neighbor, who he then seduces with pity and broken jokes, where we are then treated to a sex scene where we get lines like ,"Then shut up and kiss me some more, sexy!" For a craven image, he somehow buys an enormous block of marble, learns how to sculpt marble, and carves a Berniniesque statue of God plowing a woman in the ass while drunk. Sounds amazing, but it's presented with an utter lack of humor, a deadly serious scene that is intended as a dramatic affront to a higher power. Broad statements are made like "all anarchists are atheists, but not all atheists are anarchists" and that the difference between communism and anarchy is negligible (are you aware of what these words mean?), with all of the confidence and arrogance of a teenager who just read the cliff notes to Beyond Good and Evil. My first impression was the book was written by a lifelong devout Christian, the tone, and rhetoric comparable to Chick tracts, but by the end I couldn't tell what the experience the author had with the religion, as a fellow Bastard pointed out to me that the story seems to misunderstand parts of Christianity that are dealt with in Sunday school. As evangelical as the book comes off as (despite the sin and sex contained), it feels written by a born-again convert who found God yesterday and immediately started badgering his coworkers about going to church. All the while we are supposed to feel pity for this infantile schmuck of a character because his wife and kid, who we never meet, died in a cliche-crash. Tears are shed over graves and family photos, followed tightly by howling at the sky, demanding attention from a higher power, before robbing a collection box at church and stuffing lace panties in an altar. This is a teenager's reaction to the unfairness of the universe, not someone exploring the meaning of life. These are all questions a pastor has answers for, and when it comes to the existence or non-existence of god, you just want to slap this guy and tell him to shit or get off the existential fence.

Full disclosure, atheist here, which some might see as a disqualification for reviewing this wreck, but here's the thing: nobody grows up in America not having questions about God unless you were sheltered from doubting doubt by evangelically progressive parents. I talked to God even after I stopped fully believing in him up to my late teen years, not religious but incapable of truly internalizing alone in the universe. Having walked my own spiritual journey to absence, I can appreciate stories told by believers without relating to their conclusions. Faith in creators is a vital part of the human experience for most of mankind, an integral part of nearly every culture in history, and an unavoidable component of the fabric of the world today. Were it not for the avoidance of anything divisive to the beige entertainment consuming audiences of this country, it would be surprising we don't get more stories that address faith as a factor. That has no bearing whatsoever on this book. I only have a passing familiarity with the scripture, and even I know almost everything in here is bunk, from the extremity of the crimes (licentious thoughts can count as adultery in some readings of the Bible) to seeming to misunderstand the definition of the word "graven." There's at least a surprising attempt to clarify the position of moral atheists/anarchists near the end, which seemed out of character for the book's bluntness, but of course, this is handicapped by the equivalating of LaVeyan Satanism with secular humanism, but hey, potato poh-tah-toh. Right?

This book is a laugh and a half, and if you enjoy the acquired taste for funny bad you should give it a go. I can't wait for a second volume. Even if we don't get sent one for review (which, face it. Why would they?), I'll probably shell out a few shekels of my own to read it. It's usually admirable to try to do something ambitious with small press comics. Lord knows plenty of people are content to chase Bendis's coattails instead, but this is the philosophical equivalent of retweeting a misattributed Gandhi quote as your thesis. Still, when I kneel by my bedside tonight to give thanks to the Almighty, I'll be sure to put a word in for giving me a terrible comic that I could enjoy the whole way through for once.

[su_box title="Score: 1/5" style="glass" box_color="#8955ab" radius="6"]

Breaking the 10

Writer: Sean Michael Wilson

Artist: Michiru Morikawa

Publisher: NBM Publishing

Price: $11.99

Format: Hardcover; Print

[/su_box]